Science does jello

Are you down and blue, and don’t know what to do?

It’s been a while since I last visited the happy world of jello (see my previous posts on the subject under the category “food”). But take heart—it’s jello time again at neo-neocon.

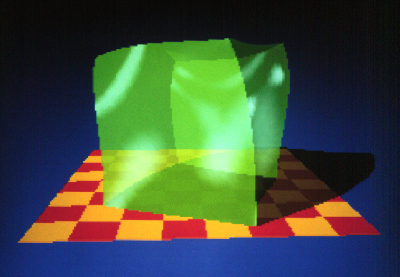

I thought I’d pretty much exhausted the jello archives at Google, searching for jello images to brighten your day. But here’s a new one:

It’s from graphics artist and former computer science professor Paul Heckbert, whose jello-besotted page can be found here. It illustrated a study by Heckbert that appeared in 1987 in Computer Graphics magazine.

Here’s a sample of Heckbert’s instructions on how to create your own jello images in just a few easy lessons, for those of you who care:

To model static Jell-O ® we employ a new synthesis technique wherein attributes are added one at a time using abstract object-oriented classes we call ingredients. Ingredient attributes are combined during a preprocessing pass to accumulate the desired set of material properties (consistency, taste, torsional strength, flame resistance, refractive index, etc.). We use the RLS orthogonal basis (raspberry, lime, and strawberry), from which any type of Jell-O ® can be synthesized [Weller,1985]. Ingredients are propagated through a large 3-D lattice using vectorized pipeline SIMD parallel processing in a systolic array architecture which we call the Jell-O ® Engine. Furthermore, we can compute several lattice points simultaneously. Boundary conditions are imposed along free-form surfaces to control the Jell-O ® shape, and the ingredients are mixed using relaxation and annealing lattice algorithms until the matrix is chilled and ready-to-eat.

Previous researchers have observed that, under certain conditions, Jell-O ® wiggles [Sales, 1966]. We have been able

to simulate these unique and complex Jello-O ® dynamics using spatial deformations [Barr, 1986] and other hairy mathematics….

Somehow I think the above is at least partly tongue-in-cheek. But with computer folk (and jello), it can be hard to tell.

Well at least Jello has a modicum of “transparency”

Jello for President!

I’d vote for it !!

Jello Biafra?

Well, why not?

Dang lattice algorithms.

Hi neo! I guess I’m becoming your resident software guy or something. Anyway, Heckbert is, completely characteristically for him, computer geeks generally, and computer graphics geeks especially (Pixar’s graphics rendering technology, pre-RenderMan, was called REYES, which stands for “Renders Everything You Ever Saw”), being semi-facetious… but only semi. Computer graphics has always been about simulation, and simulation means understanding the reality of what you’re representing well enough to be able to approximate it in mathematical logic, which is the lingua franca, if you will, of computers. Basically, computer graphics people have to know a lot of optical physics and, these days, plain ol’ physics, to do what they do. And heaven knows Jell-O&tm; makes a great physics study.

On that note, something that folks outside the field may not realize is that each and every Pixar short study ever made was made to showcase a new technological development in their rendering technology. Part of John Lasseter and Co.’s genius lies precisely in their ability to come up with stories that everyone can related to, but that in some concrete fashion wouldn’t be possible without the technological innovations. As a consequence, limitations in any given short often have a direct impact on the technological advances seen in later shorts. For example, watch Tin Toy. The thing that made us graphics geeks gasp when this short was first shown was the irregular refraction through the cellophane wrapper on the box when the baby shakes it—that was novel, to say the least. But notice that the baby needs to wear a diaper, and then notice that, as John Lasseter put it in an interview, the “diaper” isn’t a diaper at all: it’s a helmet. That is, it’s totally rigid, because they didn’t know how to model the physical dynamics of cloth at the time.

Now fast forward to Geri’s Game. Notice that Geri wears a suit, and stands, moves, sits, etc. with his shirt, tie, coat, and pants behaving entirely appropriately. That’s because Pixar had learned how to do what’s called “physically-based modeling” by then, based on Lasseter’s frustration with the helmet on the baby’s butt in “Tin Toy.” In another amusing interview, one of the modelers for “Geri’s Game” complained that in the past, he just wouldn’t bother modeling anything that didn’t appear in the frame (if no one will see it, why bother modeling it), but with physically-based modeling, you have to model things that don’t appear in the frame, because they’re still physically influencing things that do appear in the frame, thanks to their weight, tensile strength, friction, movement dynamics, and so on.

That’s probably more than anyone wanted to know, but that’s what you get for posting something about software and graphics. 🙂

What a hoax! This is a slight rewrite of a jello recipe from Gourmet Magazine.

My dad always called jello “nervous pudding”.

That Jello article is completely tongue in-cheek!. Its famous in computer graphics circles.

It was tongue-in-cheek in 1987, yes… but now soft-body dynamics is even included in popular open-source physics engines, and rendering the results is supported in a variety of ways. So think of Heckbert’s article as speculative fiction, if you will… 🙂

Apparently green jello and green cellophane share the same systolic array architecture.

One more little point that the graphics geeks forgot to mention: that checkerboard ‘floor’ has a long history in computer graphics demos. It’s used to demonstrate that the algorithm can show reflections and refractions.